Does Your Hiring Process Resemble Election Day? Two Reasons That’s a Positive Comparison (and Two It’s a Negative)

Typically, in an election year at the four-year mark of a president’s term—where there’s no certainty the administration will change—many US employers tend to delay their decision-making processes. This year, however, much like the election itself, the hiring process has already had to adapt to several changes.

That got us thinking about the many other ways your hiring process might resemble the upcoming election. Some are positive and reflect the true beauty that is selecting the right person for the job. Others are not so positive, and demonstrate the potential for confusion and disarray if you don’t carefully structure your decision.

How Does Your Hiring Process Mirror the Election?

See if your current hiring decisions are putting you on the positive or the negative side of our comparison:

- Negative—You have far too many candidates. Each year, it seems as if political parties without an incumbent in office produce more and more candidates for the American public to choose from. In 2020, there were a staggering 27 major Democratic candidates—far exceeding the previous record of 17—making it difficult for voters to remember the name of each candidate, let alone the platform. When it comes to hiring, while it’s essential to widen your pool initially, when you get to the interview/selection stage, too many finalists can breed confusion and lead to hiring the wrong candidate.

- Positive—You know which skills are important for your potential candidates. In a presidential election, there’s a clearly defined set of skills we all expect a potential candidate to have—character, integrity, excellent communication skills, crisis management abilities, great with foreign policy, business acumen, and the list goes on. It’s a basic expectation that our president can utilize the necessary skills to further our country’s goals. Similarly, if you have clearly outlined a set of skills necessary for your potential hires to help your company further its goals, you’re more likely to hire talent that can accomplish them.

- Negative—You risk missing the most qualified candidates for the job. There are very few individuals with each of the skills necessary to achieve excellence as an American president, and they may not be the ones who apply. We’ve all weathered a few election terms where it seems like none of the finalists were qualified for the job. If this is consistently the case with your hiring process, you are likely neglecting the tools necessary to find and select qualified individuals.

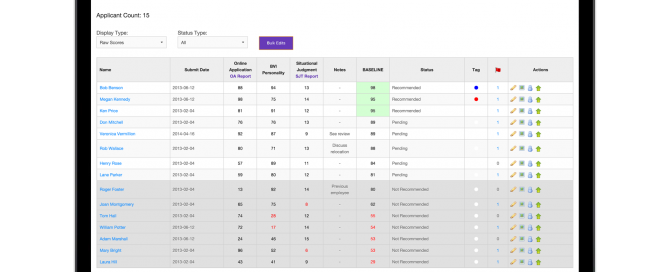

- Positive—Technology is improving the process. Today, we know more about each presidential candidate and their respective platforms than any group of voters in history. In a year marred by COVID-19, many of the traditional accouterments of a presidential election would not have been possible in the first place without the use of technology. Similarly, we live in an age where you have the necessary technological tools at your disposal to screen applicants, identify candidates with your required skills, and hire the best-fit talent for your organization.

If you find yourself without a clearly defined skill-set in mind or lacking the tools to help you identify the candidates that are most likely to become a lasting, positive addition to your team, contact Stang Decision Systems. Our innovative HireScore platform can ensure that you elect to hire the right candidate for your organization.

Resources:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/us/politics/2020-presidential-candidates.html