Sports Analytics Field Trip

By Scott Birkeland, Ph.D., Vice President of Stang Decision Systems

I recently attended the Midwest Sports Analytics Meeting in Pella, Iowa. Thanks to Russ Goodman and Central College for putting together fun and informative sessions. This conference not only gave me an excuse to hang out with my former college roommate (St. Thomas math professor Eric Rawdon), but it also allowed me to see, first-hand, some of the cutting-edge research that is taking place in the field of sports analytics.

Eric Rawdon and me at the Central College entrance (I’m on the left).

During the conference, I attended a variety of presentations. Some of the topics included measuring how teams deliver value to fans, an analysis of strike zone errors in MLB, ways to differentiate offensive explosiveness vs. offensive efficiency in college football, software that helps coaches create data-driven practice plans, and several talks that used NFL play-by-play information to analyze tactical decisions (e.g. win probability at various points in a game, fourth down decisions, field goal accuracy, etc.).

All very interesting and thought provoking topics (at least to me!).

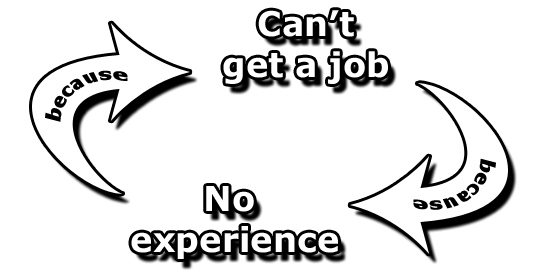

As I reflect on the conference, one of the big takeaways I have relates to decision-making and why it is that those involved with sports teams often don’t use the information that is available for them to make optimal decisions. An example that was frequently discussed during the conference is the debate in football about “going for it on fourth down.” Historically, coaches have preferred to punt on fourth down, even though, in many situations, the data suggests that they shouldn’t.

With all the analytics that are now available it is surprising how often teams go against what the data say they should do. This is true for more than just “going for it on fourth down.” It is true for drafting strategy, negotiating player contracts, preventing injuries, and developing optimal practice plans–just to name a few.

Throughout the conference, I had several discussions with folks around why teams do not consistently use analytics to their advantage. A couple of reasons were repeatedly mentioned.

First, people who are coaching and/or managing teams often have a sports background, but not a math/statistics/analytical background. Because of this, they do not necessarily understand the methodology behind the numbers. And, given their role as a leader, they must be able to convince their team why they are taking the actions they do. If the leader of the team doesn’t understand the data or how it was generated, it becomes more difficult to inspire the team to act based on that information. Coaches tend to rely on what they know best, which often means doing what they’ve always done and not using analytics.

Second, many pointed out that because coaches’ decisions are so closely scrutinized (especially in major professional sports) that if they make a non-traditional decision, they leave themselves open for significant criticism from fans and the media–even if the decision, from a data analytics perspective, is the correct one. Therefore, it is often easier and more comforting to make decisions based the way it has always been done rather than do something different. As one person put it, “it is hard to get overly criticized for doing something that everyone has been doing for the last fifty years.”

From a coach’s perspective, I can appreciate these reasons. At the same time, I also realize that it is important to utilize any advantage that you might have, even if it is something that might stretch your comfort zone. I believe that we all need to question the way things have been done (whether you are working for a sports team, a Fortune 100 company, or a mom and pop company) to see if there is a different strategy that gives you a greater likelihood of succeeding.

At its core, that is what data analytics does. It allows end users to gain competitive insights. Oftentimes, these insights contradict conventional wisdom. In my view, this should be viewed as an opportunity rather than a threat!